UNFOLDING THE MYSTERIES OF ORIGARAMI

Conveniently following on from my recent review of Daimon Brewery’s delicious Road To Osaka Nigori, this week I lucked out by stumbling across a just delivered consignment of Origarami Namazake.

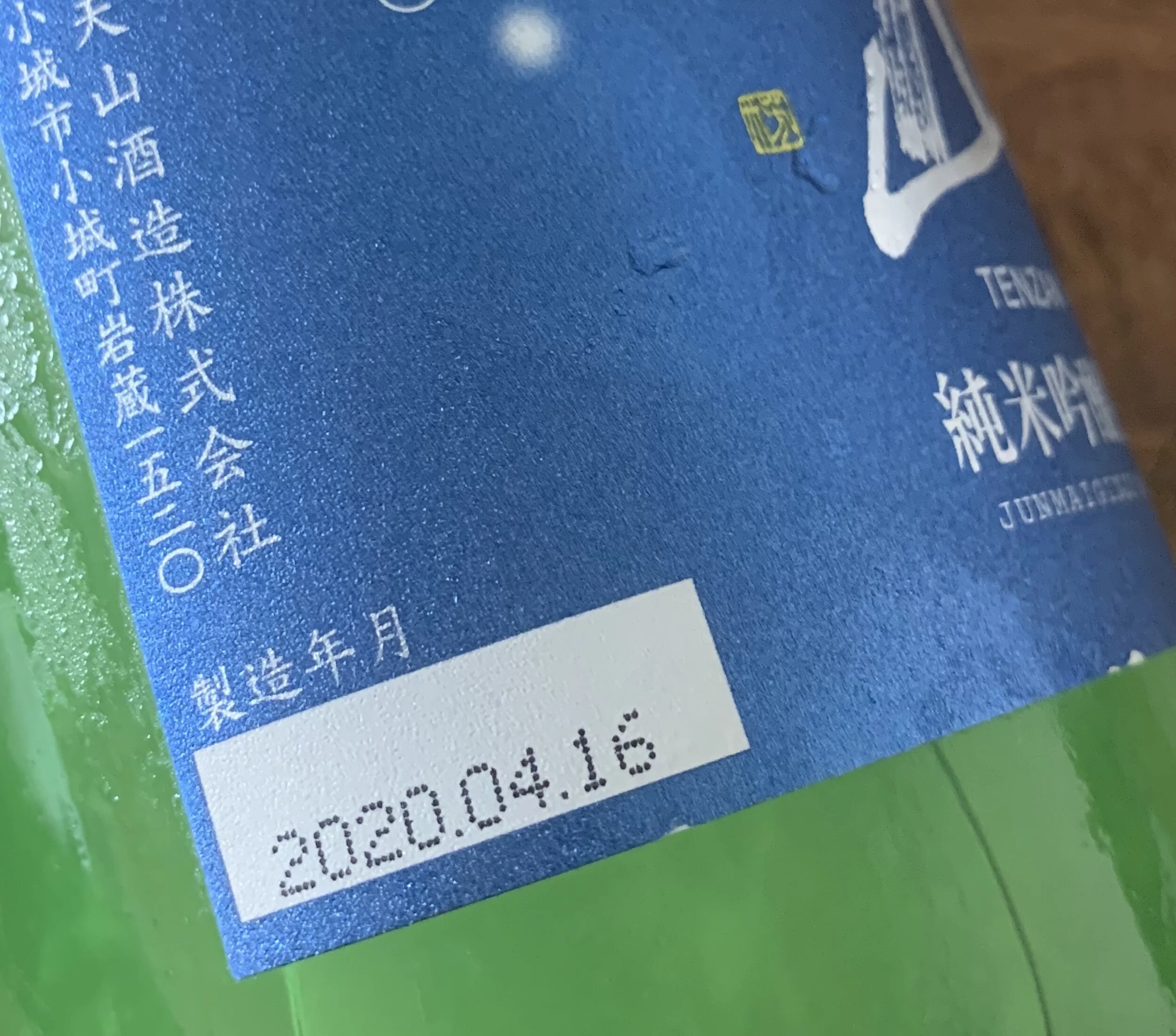

I was excited to see the Tenzan label emblazoned with a NAMA (生) and 2020.04.16 date, that’s pretty fresh for us here in Hong Kong (and really fresh for Hong Kong given all the virus-related delays), so this should really be a treat. In fact it’s only shipped from March each year, and in limited quantities. Maybe I should have bought more, I ask myself, ignoring my Sake stash in the refrigerator.

A whole lot of ori swirling about

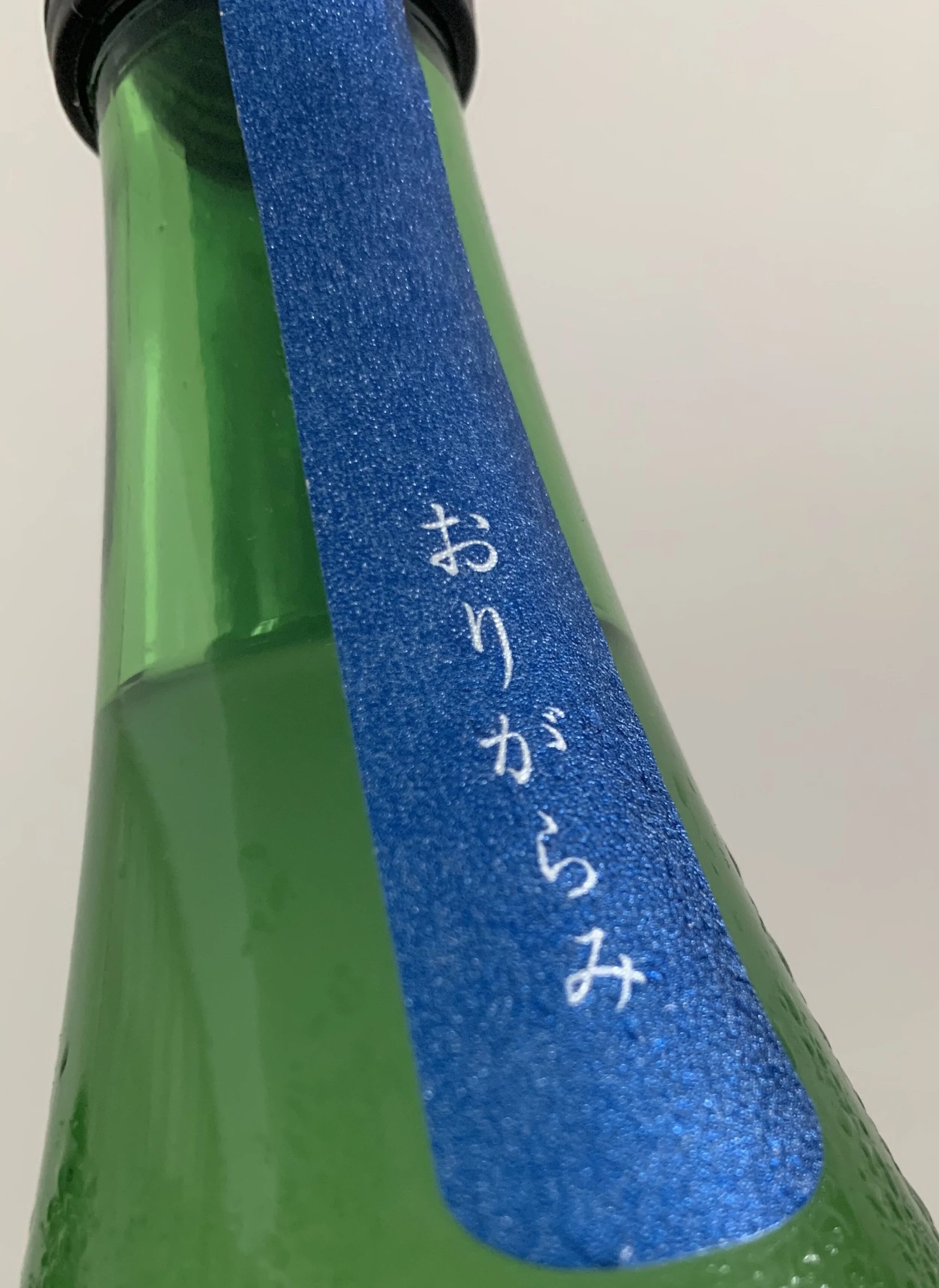

The bottles were also well refrigerated - not always the case sadly - so I’m expecting some true Nama characteristics, normally the icing on the cake to drinking in Japan. The bottle is also emblazoned with a glitzy おりがらみ, helpfully translated to Origarami on the price ticket at the store.

As I understand it, an Origarami is quite simply the pressed Sake (i.e. filtered to some degree, but filtered nonetheless, in accordance with industry regulations) that has been returned to the tank, now of course without its Sake-kasu but, crucially, it doesn’t spend enough time there for the ori to settle. For non-Origarami Sakes, the ori would be given the time to slowly meander their way down to the bottom of the tank in a process call oribiki.

These ori are a mixture of tiny rice (kakemai and kojimai) and yeast particles that are small enough to sneak through the pressing stage. They make any just filtered Sake a little conspicuous next to the perfectly clear liquid we’re used to pouring into our cups.

Oribiki migration complete, the clear Sake can be tapped off and the mass of ori particles extracted from the bottom of the tank. To make this easier for the Kura, chemical catalysts can be added to the filtered Sake to speed up the sinking process, clumping particles together to effectively weigh them down.

Tenzan’s bottle (top) and a clear Sake (below) - this difference is clear (sorry)

But I find myself scratching my head. Surely with all the Sakes that have gone fridge -> ochoko -> trash over the last few years, I must have had an Origarami? A flick through my Sake scrapbook, bloated with badly steamed off labels and over-zealous use of glue, suggests not. Or maybe I liked it a bit too much.

So, let’s assume, this is my first Origarami. And I’m excited to see how it stacks up against the Nigori. Sure, the Nigori spectrum of ‘body’ and particulates is a wide one, and there is of course a range of ‘haze’ within Origarami, albeit less broad, so this is just a generalised observation.

Factoring in differing daylight levels and inconsistent focusing, the liquids of both Road to Osaka (left) and Tenzan’s Origarami (right) are pretty close in appearance

I’ve tried to snap it in the same pose as I had the Road To Osaka to compare and it’s almost indistinguishable from the Nigori, which harks back to my comment in the previous paragraph about breadth of options. Daimon’s is at the light/delicate end on the Nigori spectrum.

One thing you won’t clearly see before opening, which surprised me (and the carpet), was the sparkling nature of this Sake. Having given it a gentle inversion or two to mix the ori back into the whole 720ml, it leapt into life as I opened it. Looking back at my WSET categorisations, this is an aggressive mousse. This bottle shot, having mopped up, gives you some idea.

The offending bubbles

So to the tasting. Finally. As we know with Sake there are always exceptions but if it’s playing ball, I’m expecting rice-forward flavors, to a level more than clear Sake, but less than Nigori. However as it’s also Nama, that ricey predominance may be subdued somewhat by fresher, vibrant, and fruitier aromas (it is a Ginjo too).

On the nose there is rice, for sure, but with a decent hint at fruit, not least banana, maybe melon. My fellow taster and wife suggested bubblegum, and she’s right. On the palate? It’s fizzy, yup, but the fruit seems to have gone into hiding. The banana is trying to venture out but it’s bran, brown rice savoury all the way and I get a little lactic note. Not the usual mozzarella or soft cheese but more a hard cheese, or even said cheese’s rind.

Acidity is there but quite low (just 1.6 on the nihonshu-do). But I like it. Really fresh, naturally, and looking now I read it described as:

A refreshing sparkling Sake with a slight sparkle and plenty of shush.

I also see it’s priced at ¥1,600 in Japan, nearly half what I paid for it here of course but I’m prepared to grin through that because it’s probably the nicest sparkling Sake I’ve tried, albeit there aren’t all that many out there. It’s a lovely summer drink or aperitif and as one of only a few to win an inaugural IWC (International Wine Challenge) Gold Medal for sparkling Sake, not such a bad price really.

They should put that award on the label (alongside an aggressive mousse health warning).

FOOTNOTE:

I wrote this in real time - this week’s schedule was a little chaotic - so that should explain the somewhat jerky style, I hope.

QUICK GLOSSARY:

Nigori 濁り: “Cloudy” or “milky” Sake that has some of the original rice solids from fermentation remaining in the liquid. Body can vary from simple opaque through to quite thick and porridge-like. Brewers achieve this by running the Sake through a coarser filter or by adding the rice back in after filtration. Note that Japanese law stipulates that all true Sake must be filtered

Namazake: 生酒 (生:raw, fresh, or living; 酒:sake) – in short, unpasteurized Sake

Sake-kasu: The residual rice solids (like “lees” in wine) from when the Sake is separated from the main fermentation through pressing

Kakemai: Steamed Sake rice

Kojimai: Sake rice that has been inoculated with the Koji-kin mould

Kura: Sake brewery

Ochoko: A small traditional cup, normally ceramic but can be earthenware, plastic, metal or wood, for Sake drinking

Ginjo 吟醸: Sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 60%

Nihonshu-do: The scale used to measure the specific gravity of Sake. The higher the positive number, the drier the Sake (“higher is drier” - thanks John Gauntner), and low negative numbers are representative (generally) of sweeter sake. In English, this is the SMV (Sake Meter Value).

Junmai: Sakes made with no added alcohol are Junmai, the only ingredients are rice, water and Koji mould

Sake-kasu: The residual rice solids (like “lees” in wine) from when the Sake is separated from the main fermentation through pressing

LINKS:

Tenzan Brewery

www.tenzan.co.jp

Daimon Brewery

www.daimonbrewery.com