AGE IS JUST A NUMBER

I’m hurtling towards my half century, and whilst it’s still a few years away, the writing has been on the wall for a while. In 2019 I was offered senior rates for golf in Michigan. Twice. At least there’s some silver lining to turning five-zero, I guess.

And how is it that time flies by so fast in a pandemic anyway?

But let’s change the subject matter from that milestone (probably best for my mood) to Sake, and the topic of age. No this is not a story on Koshu aged Sakes, quite the opposite. Let’s talk unpasteurised 生酒 Namazake and take a practical look at the general consensus that the drinking window is so much shorter than for hi-ire 火入れ pasteurised Sake.

Anyone new to Sake quickly picks up on a few easy to remember snippets that are, for the most part, reliable and universally agreed upon, the kind of things you’ll call on in your early shopping and quaffing of Sake. Things like: “Warm Sake doesn’t mean it’s cheap Sake” and “Sake shouldn’t just be drunk with Japanese food.” That kind of thing.

However (and this in itself is another such piece of wisdom) many will remember from their formative learning sessions too that “when it comes to Sake, there are always exceptions.” And that’s what my little tasting experiment is about today.

It’s worth stating now that I love Namazake. But not everyone does (see, there’s an exception right there) in that some think that the flavours on offer due to its Nama state of raw freshness mask and overwhelm the true flavours of the Sake. But I like it, that brashness and wildness remind me that this stuff is indeed alive and super fresh. It transports me to cold damp breweries in Japan, open to the elements, and to experiencing as closely as you generally can Sake straight from the tank.

As a Sake beginner I liked the fact too that many brewers would kindly print a 生酒 somewhere clearly on the label, or even an almighty 生 on the lid. A knowledge crutch as you navigate your way through what is really quite a steep learning curve with significantly more elaborate kanji to get to grips with. (I’m talking about you, jō 醸).

By and large in the same sessions, chapters or YouTubes you’ll also be told that the shelf life of Namazake is short and should ideally be consumed within twelve months, keep it refrigerated and drink it within a few days of opening. Some specify six months, not the twelve, but either way it all seems a bit time sensitive. There are even some Sake industry folks in the city here that insist that Nama must be consumed within three months after the bottling date.

Of course I agree that time, temperature and light all have an impact on Sake, pasteurised or unpasteurised, and there is unequivocal science to explain this, and much of that is simply common sense. But can you cheat the science?

“When it comes to Sake, there are always exceptions.”

I have already had a little play with temperature and light in an earlier article (here), time too in some ways, and both showed their respective potential for causing deterioration. However by taking things to the opposite end of the spectrum, and creating idyllic conditions for Namazake, is it possible to extend life beyond the three, six or even the twelve months?

Thankfully, I have help to hand here. To date, no Namazake has survived much longer than a month in my fridge. I told you I love the stuff. Lucky for me, the good guys at Koji Sake here in Hong Kong are meticulous about temperature at each stage of the supply chain, from Kura to kitchen, keeping it chilled on its journey until it gets plonked in my fridge and that little light goes out (it does go out, right?).

Instagram: @scmpnews

Refrigerated transportation in Hong Kong is really important, particularly in the Summer when the mercury rises and the humidity kicks in. The city experienced its warmest spring on record in 2021, with a mean temperature of 25°C, and the South China Morning Post warning of a “sweltering summer ahead.” So for Namazake and premium Sake, Koji Sake uses refrigerated delivery trucks whenever possible to ensure that the quality is not compromised.

The guys at Koji Sake recently identified some Namazake that is well over the twelve-month hill and asked me to help ratify the belief and confidence in their storage set up.

“I still have some Nama that is older than 1 year old. Since we store it properly, I strongly believe it's perfectly fine in terms of quality, but most people maybe will think otherwise, would be nice if you can try and see if you agree.”

If only all my instant messages were so nice to receive.

So, here’s the key numbers for today: 2019.3, and as ever it isn’t immediately clear what this refers to. Sure, it’s March 2019 and in all legal likelihood, this date on the bottle is the bottling date as breweries tend to have their Sake bottled just before shipping. But sometimes they’ll lay it down to settle a little in bottle, then pull it out of storage, label it then and date it, finally shipping it off.

But this is Namazake, the most feasible story is that it was bottled and shipped in March 2019. Less likely, but possibly, it chilled out a bit, literally, and was labelled, dated and shipped six months later. Either way, this stuff is at least 21 months old. Lucky for me, Koji Sake has kept it stored between 0°C and 2°C.

Well folks, panic over. This Sake is showing no signs of age and remains a Nama through and through. I could even argue that it could develop nicely into something even more special after another session in the fridge.

It remains untamed. Sure, it’s dry but that’s a given with the 辛口 Karakuchi on the label. The liquid is clear - my photos aren’t doing it justice - and even clearer and brighter maybe than the Sake beside it - another Namazake, but over a year younger (a delicious Honjozo by the way). I can still tell it’s a Junmai, admittedly I wasn’t tasting this blind, but there are some indications of richness, acidity, lactic notes and true rice characteristics.

I look further into my tasting notes and they seem pitifully uninspiring on this in that they just reel off all the textbook characteristics of Namazake - clear, crisp, clean, wild - but I guess that simply goes to prove the point: we’ve done it, we’ve cheated science

Or maybe we didn’t, is this just one of those exceptions? Who cares, it’s exceptional.

FOOTNOTE:

Got to love an experiment!

Try for yourself the well-loved Sakes curated by Koji Sake, link below.

LINKS:

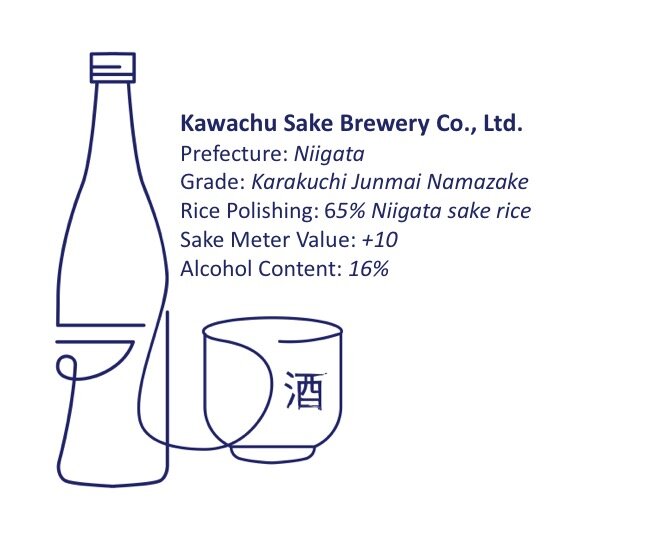

Kawachu Sake Brewery Co., Ltd.

www.soutenbou.jp

1677 Wakinomachi, Nagaoka-shi, Niigata-ken 940-2306, Japan

Tel: +81 (0)258-42-2405

Koji Sake

www.koji-sake.com & www.facebook.com/KojiSakeLimited/

Instagram: @koji_sake

Phone: +852 2111 3095

Email: sales@koji-sake.com

QUICK GLOSSARY:

Koshu: General term for aged Sake

Namazake: 生酒 (生:raw, fresh, or living; 酒:sake) – in short, unpasteurized Sake

Hi-ire: Literally translates as “put into the fire” but in the case of Sake refers to Sake that has been pasteurized

Kura: Sake brewery

Karakuchi 辛口: Basically “dry”

Honjozo 本醸造: Sake made from rice at a polishing ratio below 70%

Junmai純米: Sake made using only rice, water, yeast and koji–no added alcohol (純: pure;米: rice)